For my midterm assignment, I wrote an analysis of different scenes and characters within Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and their interconnection with mysticism. I argued that the novel is a spiritual pamphlet that advocates for Protestant Mysticism and critiques the existence of Catholic Mysticism. Now I want to turn our attention to the similarities between, specifically, the Monster and painful mysticism. How does the Monster experience painful mysticism? How is this similar, and different, to the feminized mystical experience of medieval mystics and their emotional embodiment?

It is not only Frankenstein’s lack of accountability and control that forced the Monster to become a creature that declares war against his own creator, but also the intense feeling of loneliness he slowly started to embody. As his journey into manhood erupted, everyone around him became frightened of him. His monster-like appearance in no way made him look sweet and desirable to the outside world.

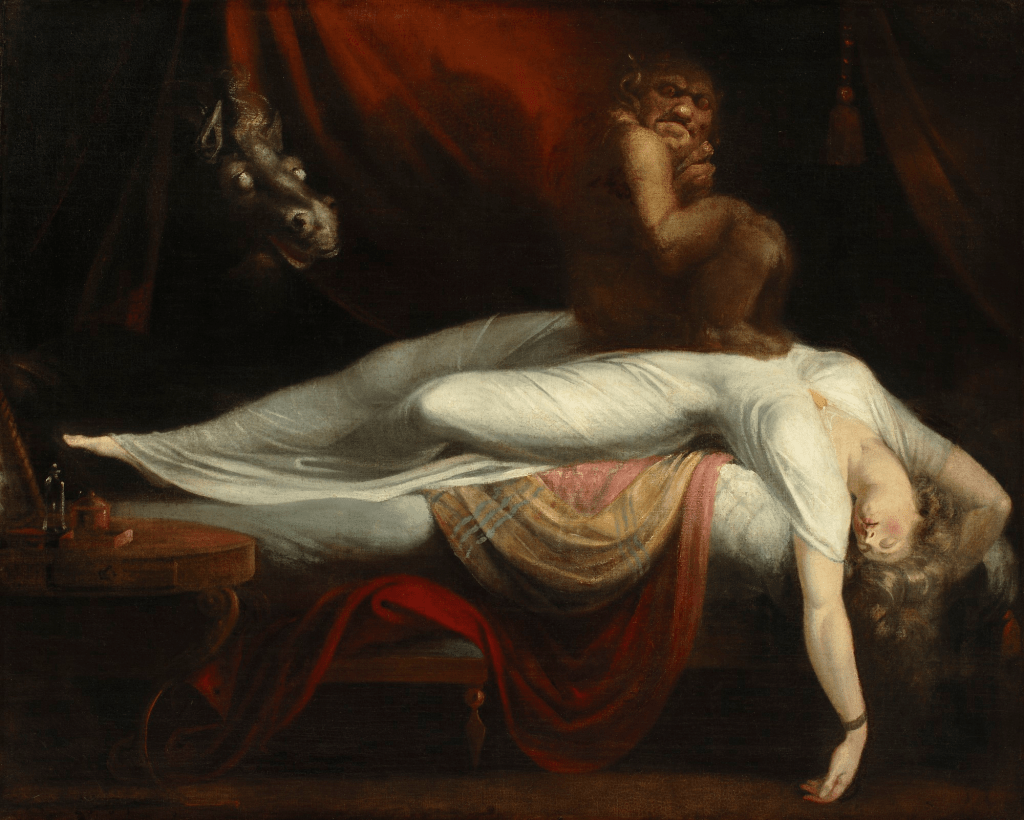

Figure 1.0. Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781). There is no precise interpretation of what is actually happening in this painting; however, some scholars have noted the similarites between this painting and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Popular among Gothic culture, perhaps some of her inspiration came from paintings like this one?

Rejected from both his creator and society, Frankenstein develops what I like to call, once again, painful mysticism. As I mentioned in my previous post, many female mystics felt literal pain when cultivating their affective piety. This is of course due to the embodiment they desired to feel in connection to Christ’s humanity. If Christ suffered, they would suffer as well. Now, how does the Monster fall into this category? Well, as the novel turns to the Monster’s recall of his experiences he starts to embody the painful experience of our Fallen Angle: Satan.

Let’s take a look at two details from different chapters within the novel. The detail from chapter 10 reads as follows:

“All men hate the wretched; how, then, must I be hated, who am I miserable beyond all living things! Yet you, my creator, detest and spurn me, thy creature, to whom thou art bound ties only dissoluble by the annihilation of one of us.”1

The other detail, from chapter 15, reads as follows:

“Many times I considered Satan as the fitter emblem of my condition, for often, like him, when I viewed the bliss of my protectors, the bitter gall of envy rose within me.”2

Shelley reminds us that loneliness is the greatest danger to humanity. The Monster, firstly, makes it clear that there is a major link between him and Satan. Both the Monster and Satan were hated as “wretched” things in all of humanity. And then, both the Monster and Satan are tormented by extreme loneliness as they are shunned from the reality of moral society. Most importantly, he feels this embodying persona just like any female mystic would feel her pleasurable, spiritual, pain. The Monster feels his pain through his loneliness, just like female mystics have (take the example of Julian of Norwhich and her station as a ‘living dead’); The Monster puts himself into the shoes of a figure from the Bible, Satan, as most mystics have done (take the example I gave in my earlier post of Margery Kempe and her placement in the miracle of Christ’s birth); And most importantly, the Monster, makes sure to embody the actuality of Satan’s pain as an outcast, just like many mystics have done with other figures of the Bible.

The only contrast, however, that I have seen between the Monster’s Mysticism and the Medieval female mystic is the enjoyment of their spiritual, ad physical, pain. Unlike a female mystic, the Monster does not find his pain pleasurable in the same way. The Monster experiences deep emotional and physical pain as a result of his rejection by society and his longing for acceptance. His suffering is a source of anguish and torment, rather than pleasure. In contrast, a female mystic who practices affective piety may find a sense of pleasure in the pain she experiences as a recluse of her intense emotional connection with the divine. This pleasure, unlike the Monster’s, is derived from a deep spiritual fulfillment and union with God. Nevertheless, we do see the Monster experience his mysticism through a similar tendency: a drive for connection.

Leave a comment